Straight Razors

This month we will be taking a deep dive into razors, straight razors to be specific. Since the 1600s razor sharp blades have been utilized to remove the hair from one’s face. Razors have not changed very much over the centuries, an extremely sharp blade, small blade and handle, folding into protective handle scales. Over the intervening centuries and peaking in the 1900s this simple style has been refined to an elegant slim and thin blade that is easy to hold in the hand and removes facial hair with surgical precision. It is not only the style that has been refined but the materials that make up the modern razor have also been updated from the simple iron of early renaissance era to stainless, pattern welded, and the multi-bar steels of the modern era. Handle construction and materials have also been modernized from simple woods to water resistant materials that can last as long as the blade.

In the 1600s razors took the shape of a miniature hatchet, I have made sharp axes I can’t imagine shaving my face with one. In the 1700s the shape of the blade elongated into more of a wedge shape blade wider at the tip and narrower at the pivot point (as seen above). The blade was ground thin and flat without the tail seen on more modern razors and the scales of the handle were straight and flat. This style was developed by Robert Huntsman of Sheffield, England. The early 1800s saw a few changes, a shoulder began to appear creating a transition between the blade edge and the tang. Razors saw their first hollow grinds, jimping appeared along the top and bottom of the tang for better grip. This period also saw about a ten-year fad of large wedge-shaped razors utilized by barbers, think Sweeny Todd.

Razors continued to refine in shape, hollow grinds, and materials throughout the end of the 1800s and early 1900s most notably a more defined tang for the user to hold onto and “barber” notches appeared in the end of the blade.

Today custom makers create beautiful renditions of this classical shaving instrument for collectors and for those who want to experience the nostalgia of shaving with a classic razor. Recreating these classic instruments in my shop has been quite a learning experience, shaving with them has been even more of an experience and the learning curve is quick, it has to be. Next week we will showcase some makers that are out there as well as some of the popular materials that are being used.

In the early 1800s a man named James Stodart was a blacksmith in England who specialized in straight razors. Mr. Stodart was the first in Europe to take cast steel from India (Wootz) and make usable instruments from them (R.K. Danube, 2014). His straight razors made from this steel had a reputation for holding a keen edge and keeping that edge for a long time. Mr. Stodart, proud of this fact, advertised this steel on his business card (see picture). This is the first time an exotic type of material was utilized for the blade steel on a razor.

Today there are several custom makers that create beautiful works of art in the style of straight razors using many modern materials. Max Sprecher is the epitome of the aforementioned statement. He creates sleek beautiful razors with “jimping” in the form of elegant file work, his blade steel ranges from San Mai to O1 tool to Suminagashi Takefu White V2. He favors a ¼ hollow grind with various styles of points. His handle materials range from tortoise shell, to mammoth ivory, to carbon fiber, and acrylics.

Another maker is Christopher of ShaveSmith out of Colorado, Mr. Christopher is a second-generation smith who hand forges every razor he makes. He makes all styles from the larger Shefield style to the Japanese Kamasori. Utilizing high carbon steel, Suminagashi Takefu White V2, and pattern welded steel he showcases a more rustic style but is not apposed to a polished and refined look to some of his work. His handle material ranges from wood to bone to horn, he is also known to do the Ido wrap on some of his Kamasori blades.

Of course, you can also find companies that produce very good quality production (mass produced in a factory) razors as well, though these may not have the intrinsic sentimental value as one you have had custom made. At the Ogre’s forge we have dipped a toe or two into the straight razor waters, though not our most common work the razors we create, like the above companies, are made from scratch, forged in our shop, and come shave ready. One of my customers only displays his razor as he has stated it is “wickedly sharp” and puts forth a disclaimer to anyone who desires to handle it that they are “taking their life in their own hands”.

Western style straight razors have named parts much like a folding knife (see picture below), you of course have the blade, edge, point, handle, handle scales, pivot pin, and tang. Beyond that there are some additional named parts for a straight razor, the portion of the tang that extends beyond the pivot pin is the tail, the leading edge of the sharpened edge is the toe with the back being the heel, and file work on the top of the tang or bottom is called jimps. Knowing the straight razor specific parts are important as they are the portions that dictate the style of razor you have or want.

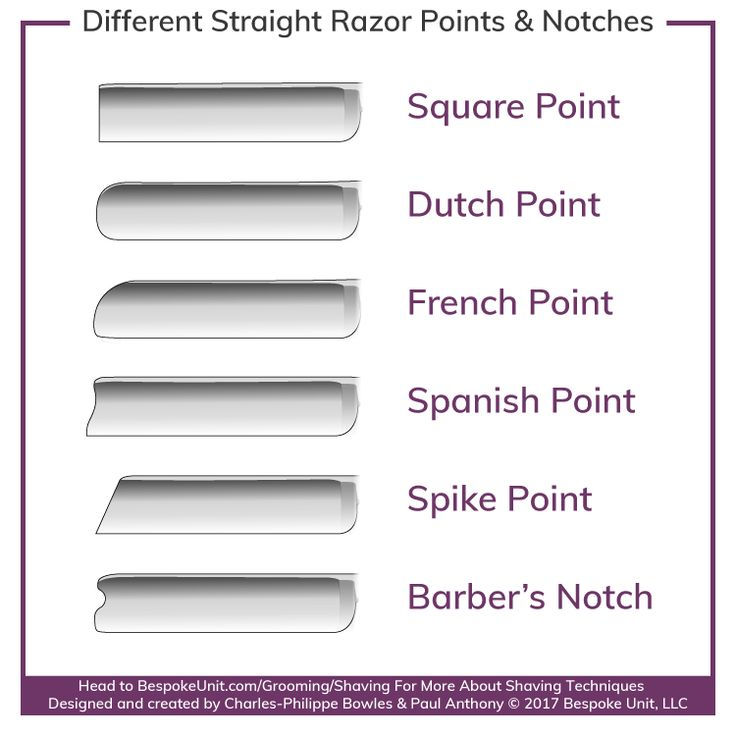

Let’s start with the tip as it is the most notable part that changes. There are six common styles of tips but are not all inclusive as we will talk about later. Square, Dutch, French, Spanish, Spike, and Barbers notch (see attached pic) are all styles of points that for obvious reasons show where they came from. Custom makers today hold with these points but some have come up with their own points such as an Irish Point that is a design of Max Sprecher noted above. Opposite of the tip is the tail, this is the end of the tang and it is important as the finger rests on the tail as one shaves. This feature can be longer or shorter depending on the style but is usually curved to fit a finger.

The width of the blades is another design structure that changes in razors, widths are measured in eighths of an inch, from 3/8, 4/8, 5/8 …. 8/8 with the last one being the equivalent of one inch in width. Custom makers do go beyond the standard widths in their respective creative styles some up to and beyond 12/8ths (1 ½) creating fun and innovative styles. In looking at blades really your imagination is your limit, clean sleek classic styles, or wild large blades that would make Jack the Ripper’s palms sweat.

The last thing that separates straight razors from regular knives is the style of the grind. Straight razor blades are ground very thin, this enables them to hold a very keen edge that is easily honed. Straight razors are ground from what is called a full hollow all the way out to a wedge or flat grind. Full hollows are a grind that removes the most material from the blade leaving an extremely thin blade for a longer length up the cross section of the blade (see attached graphic). From there each subsequent grind leaves more material in the blade until the true wedge, which is a grind that is a straight line from the spine to the edge with no hollow grinds at all. The Japanese do this but only on one side with the back side of a Kamasori left at a ninety degree from the spine and the front side of the blade ground flat from the spine to the edge, this is called a chisel grind.

On the topic of the Japanese style straight razor, the Kamasori, there are some differences between the western style and the eastern style. The Kamasori is a more refined version of the “hatchet” style found in the European Nations in the 16th century, but as the Japanese are known to do, they took something crude and perfected it. The most notable difference is that there are no folding handle scales, just the tang in various styles. These may be a plane steel tang, one with elegant file work, straight or upswept, wrapped in an Ido wrap, or covered in wood. However they are done, they do not have the folding style of the western versions. The other notable difference is that though many of the point styles can be found in the Kamasori, the barber’s notch is conspicuously absent. The blade styles can be as simple, elegant, and refined as western styles but, though it is rare, can have a bit of flair to them as is seen in some custom western styles.

댓글